I was 9-years-old when my father told me we were moving to Germany. “For a year, and then we’ll come home,” he said. He had come into my bedroom to deliver this news, and I received it head down, disbelieving, my gaze fixed on the wall-to-wall teal carpet that quickly blurred. Germany. Of all the places on earth.

To be fair, at that time, there was no place I would’ve wanted to live besides New Jersey. Maybe we could’ve been closer to the Menlo Park Mall. Actually — if we lived in the Menlo Park Mall, that would’ve been the best. The two-story, fluorescent-lit shopping complex on the edge of Edison was, in my young mind, the height of culture, a place where all the cool kids hung out, where one could avail of both Claire’s and Panda Express.

Not that I had any discretionary income. My parents refused to give me an allowance on the logic that if I wanted something, I could ask them for it, and they would decide whether or not I could have it. This, naturally, displeased me, and I looked forward to the day when I would be able to make my own money and spend it however I liked.

Despite the fact that I had zero dollars to my name, the knowledge that I would soon be ripped from the consumer culture I knew and loved hurt. How could they do this to me? What about my friends, my school? It was a short walk from my house; I had never known any other. A year, to a child, feels like an eternity, or at least, it did to me. The plan was to rent out our house and return to it in twelve to fifteen months, but I found the prospect that we would return and that our house would be unchanged dubious, at best. I felt like my life was being ripped out from under me and swapped for a new one, one to which I had not consented.

Dramatic? Yeah. As an only child, I was privileged to be the center of my parents’ universe and acted as such, a tyrant who demanded papier-mâché one day and the entire catalog of The Babysitters Club the next. Most of my wishes were granted (never did get that Barbie Power Wheels) and I do not recall showing an ounce of gratitude, accepting these gifts as if possessing them was my God-given right. (Are all children like this?)

My memory is hazy, but I think my dad left my room soon after I started crying. He did not condone tears. (He also did not like to hold my hand when we crossed the street and insisted, on our trips to the city, that I learn how to jaywalk like a real New Yorker.) It quickly dawned on me that I had no say in this matter. My dad’s job was transferring him to Germany and my mom and I were going with him, whether I liked it or not. By this point, I had traveled a fair amount. We went to India every other summer to visit family and we had recently been to Sweden and Denmark to visit a university friend of my parents. Germany was not the issue, what upset me was the record scratch jerk from my daily reality.

In my room, I recalled other words that my dad had said when he delivered the news. I would attend an international school. There would be lessons with a German tutor in New Jersey and language classes once we arrived. This temporary post was an opportunity for him, one he couldn’t turn down. I was old enough to understand the meaning of opportunity, how you’re supposed to answer when it knocks. Nothing about this move sounded cavalier. It must have been carefully considered. While my father was prone to impulse, my mom never made hasty decisions (quite the opposite, her compulsion to “think about it,” particularly with regard to clothes and makeup that I wanted to buy, annoyed me to no end).

I’m not sure how long it took, but I pulled myself together. Dried my tears, blew my nose, went downstairs. My parents were in the family room, my dad probably disseminating to my mother how I took the news. They regarded me with some surprise, perhaps assumed that I’d need longer to wallow.

“It’s okay,” I remember telling them. “Home is wherever we are.”

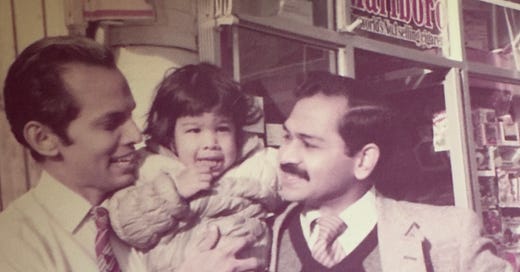

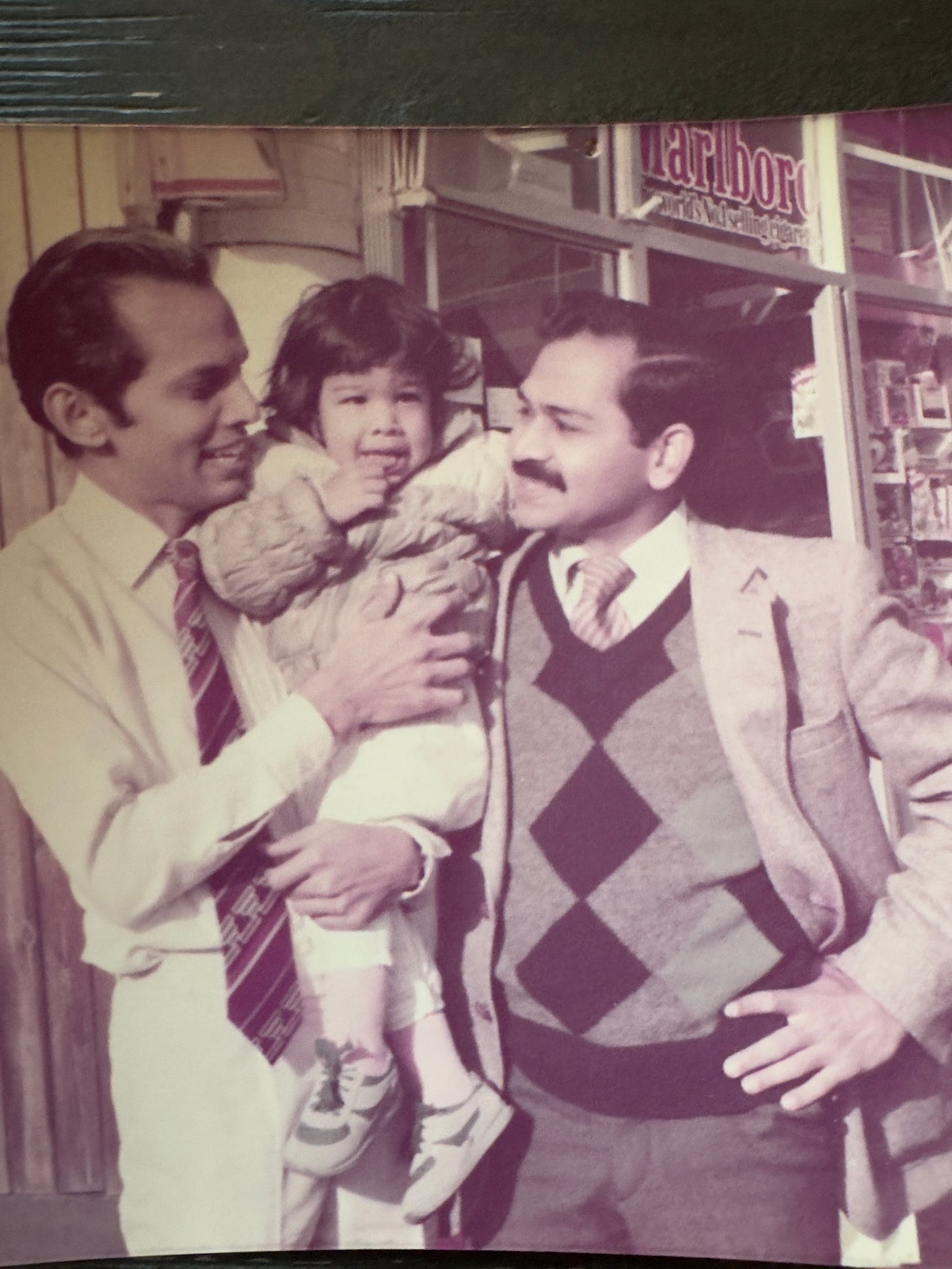

My dad gave me a pat on the back in a way that communicated pride. (This was before my parents and I exchanged hugs and “I love yous,” which, it pains me to say, I never got to say to my dad, nor he to me.)

I’ve been thinking about this episode lately, hearing the stories of friends and strangers from Los Angeles who lost everything in the fires, who are wrapping their heads around where to go, what to do. By no means do I share this reminiscence to suggest that homes are replaceable. They are not. The home that I returned to, in the summer of 1994, was different from the one that I left because I was different, I had new perspective. A year and a half in Germany changed me in profound ways, which is another story for another time.

I suppose I’m sharing this in the interest of solace. Maybe home is wherever you are. Maybe home is a state of mind.

Nice remembrances of the past❤️